Why Try? Because I Can

Number 1 in an occasional series on aging.

“If you figure I have 30 years to go, and average 30 books a year, that’s only 900 books left to read. So I should choose carefully.”

“That’s so depressing!”

The first speaker was me, maybe 10 years ago. The second, a younger friend. As it turns out, I’ve updated my actuarial estimate, because since then both of my parents died at age 91, so here in 2025 I still tell myself I have 30 more summers. (Then again, I’ll probably get killed on tomorrow’s run by a guy driving a pick-up while texting and toking.)

Newsflash: People don’t like to talk about mortality. Most don’t even like to think about it. My friend’s reaction to my book countdown was akin to that of another friend, who once immediately shut down my proposed on-the-run topic of, “Do you think you’ll know when you’re doing it that a particular run will be your final one?”

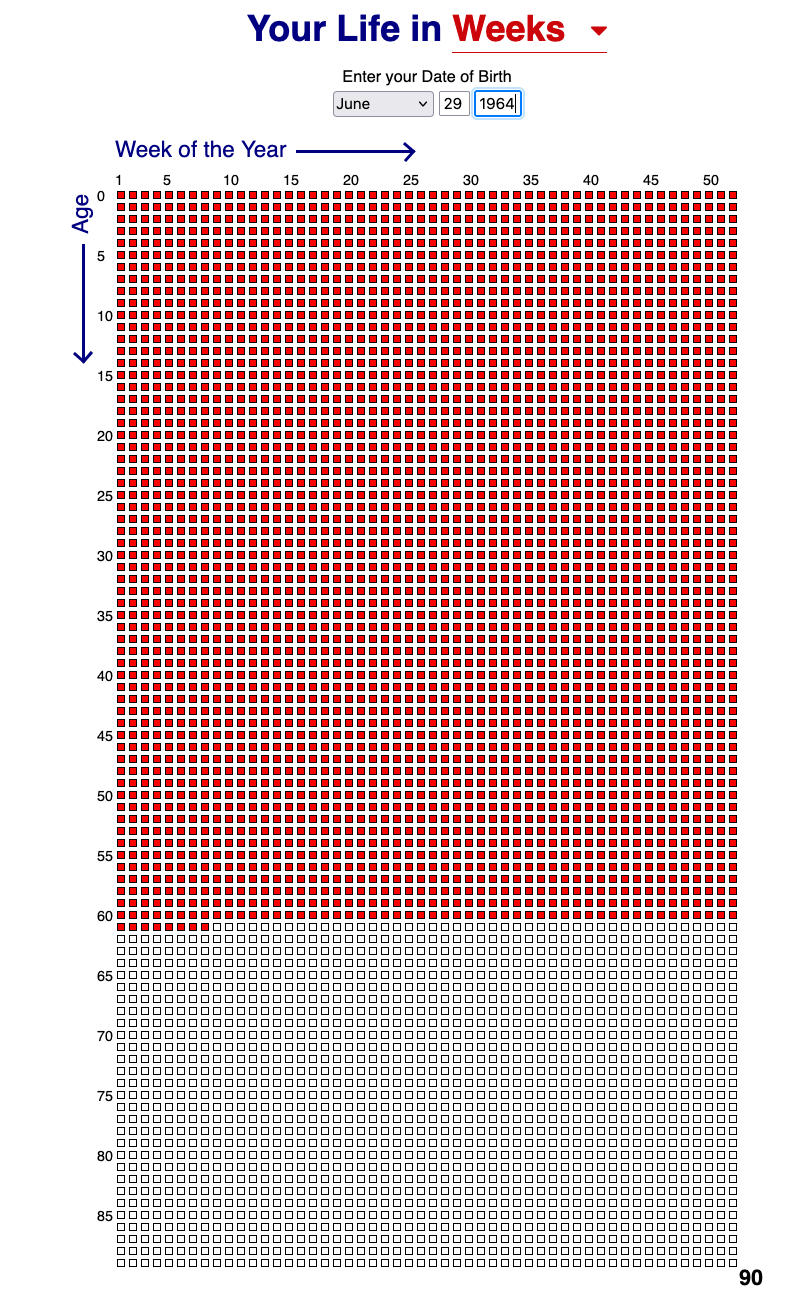

Now, I don’t sit in front of a memento mori every morning or otherwise dwell on death. But I have absorbed enough Stoicism to know I should regularly remind myself of the inevitable and then live accordingly. At age 61, I have many more days behind me than ahead, as this helpful weeks-of-your-life calendar demonstrates.

Being a lifelong runner adds an interesting twist to these reflections. On the one hand, I’m way more vibrant and capable than most 61-year-old Americans. Running about my age in mileage most weeks feels wonderful. On the other hand, I’ve been getting slower for two-thirds of my 46 years as a runner; I’ve had indisputable evidence of physical decline since my mid 30s. It’s been logical for decades to acknowledge that there will come a time when daily running won’t be a good idea, and that that watershed will devolve into an eventual end of running altogether.

This is a long-winded way to say that I’ve really been enjoying resuming regular racing this year. (Maybe when the weeks-of-life calendar is more filled in I’ll get to the point sooner.)

A little background: I haven’t been much interested in regular racing since I started to slow during the Clinton presidency. I’ve always loved running qua running, and have consistently done things that look like training (long runs, interval workouts, tempo runs, variation in distance and intensity throughout weeks). I was motivated to race a lot when on the up part of the curve—it was always exciting to think I might run faster than ever before. But when it was obvious I’d set my last PR, my enthusiasm to put that so-called training to the test deflated quickly. “Slowing the rate of slowing” isn’t exactly captivating. And when I started to compare race paces to glory-days training paces, ugh, that really didn’t set me up for satisfaction.

In 2024, the year I turned 60, I told myself that I should give racing another chance. As a teen, I always liked it when nobody younger than me beat me at road races. Maybe I would get similar pleasure from races where nobody older than me beat me.

This plan got postponed when, during a run in March 2024, my left extensor hallicus longus tendon ruptured seemingly spontaneously.

Several months later, when I got back to daily running with good volume and quality, I found my motivation had shifted. I’d been too nonchalant—or willingly oblivious—to the precariousness that underlies everyone’s running career. I found myself thinking not, “I should resume racing,” but, “I want to resume racing.”

And I was right!

I’ve relearned how to enjoy—to the extent that feeling like you’re being strangled can be enjoyed—the singular sensation of the final third of a hard race. It’s a special place far, far removed from the usual aspects of American life circa 2025. And now that I’m so much farther back in the pack, there are plenty of people to key off of to help me reach and stay in that place. This is a great contrast to even a decade ago, when, despite my PRs being older than many of the people near me, I was still wracked with thoughts like, “Really, now I’m running all out to be near a guy blasting music from the phone strapped to his arm?!”

Racing is also newly meaningful because of another seemingly depressing Stoic concept, negative visualization. The idea here is that you briefly think about negative scenarios that aren’t part of your current life, and thereby have more gratitude for your situation.

I was stretching at home before heading to the Yarmouth Clam Fest 5-miler last month when the unhelpful thought, “Why try?” intruded. I thought of my dear friend Jim Hage, a 2:15 marathoner back in the day whose 41-year running streak ended in 2023 because of a torn meniscus that eventually led to a partial knee replacement. His return to regular running has been rough, and the feeling of running isn’t as pleasurable since his surgery. “Why try?,” I asked myself again. “Because Jim would love to be able to race 5 miles faster than his daily run pace. Why try? Because I can.”

And I’ve never been happier to average 7:08 per mile for 5 miles.