Dumb Luck

Ask not, “Is this person smart?” Ask, “How is this person smart?”

I once was on the phone with a new girlfriend when she asked what color my parents’ eyes were. This was after I’d dropped out of a PhD program and had invented moving back in with one’s parents, so it was easy to say, “Hold on,” then yell, “Mom, what color are your and Dad’s eyes?”

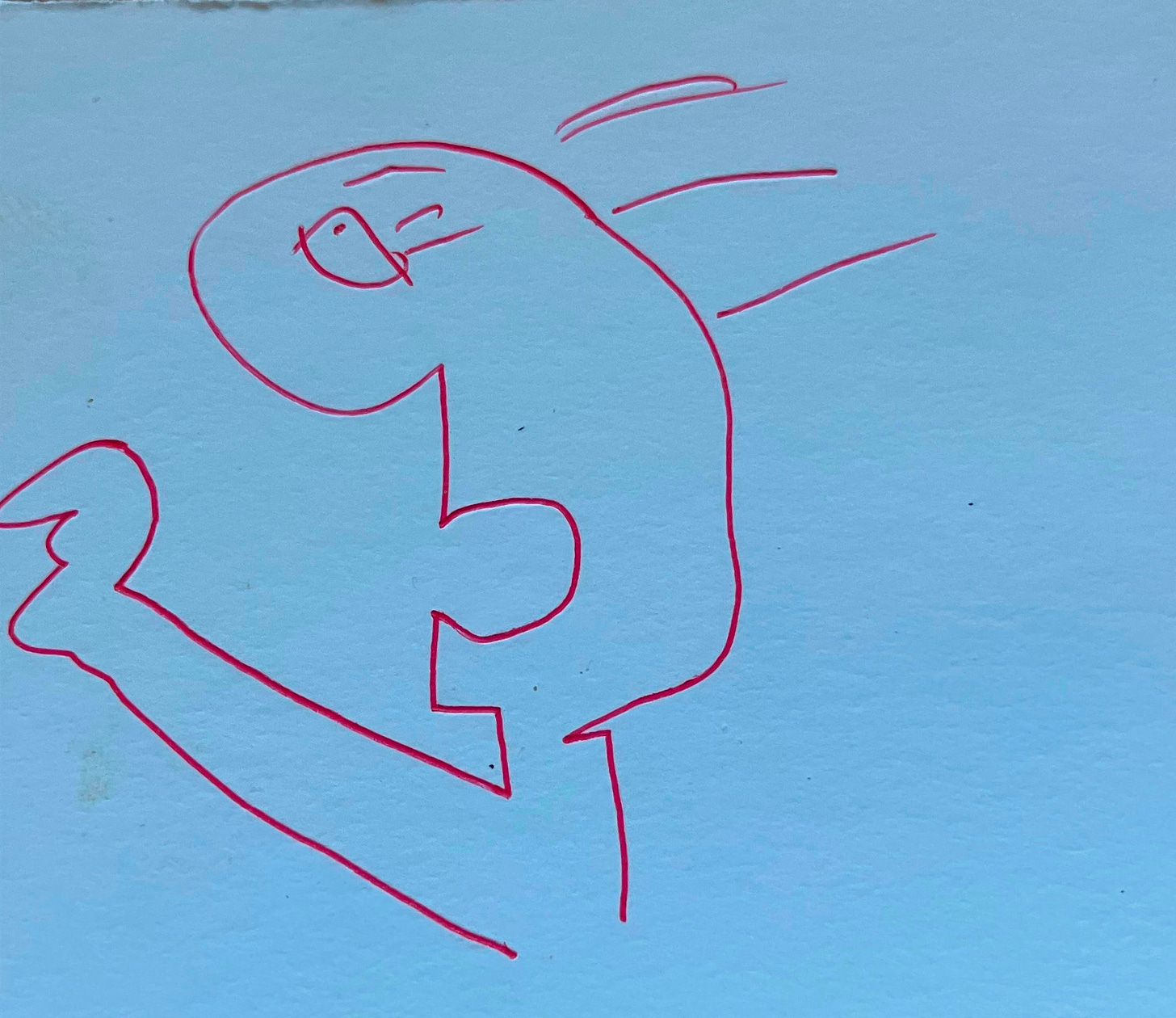

My girlfriend was amazed that, at age 24, I didn’t know the answer. She shouldn’t have been. Obliviousness to visual details is one of my specialties. If quizzed right now, I would score under 50 percent in naming the wall colors of rooms in the house where I’ve lived since 2021. A related deficiency is drawing; the gentleman below—my muse since elementary school, long before I’d seen Picasso’s Guernica—is the only thing I can do in that regard.

And spatial relations, sigh. I didn’t learn to tie shoes until third grade. That happened only because my father and I were playing basketball, I suddenly called the game off, and my father said, “I know you’re quitting because your shoe came untied. We’re going to stay out here until you know how to do it.” It eventually took, but applied only to shoes. When I had to tie knots for merit badges in Boy Scouts, I would practice for the half hour before I knew I’d be tested, eke by, and then forget it all immediately. When we took standardized tests in elementary school, I always scored in the bottom 5 percent on the spatial relations section. So, don’t ask me to help assemble even the most basic Ikea item.

The standardized test results stood out, so much so that a guidance counselor once asked my mother if I’d been sick, because they were a seeming anomaly. I was a bit of a freak in the other direction for most of public school. In third grade, I beat teachers in a spelling bee. In fifth grade, a teacher accused me of cheating on a quiz because of how quickly I’d written down Maryland’s 23 counties. (How long does it take?!) In 11th grade, I got one answer wrong all year in trig, and that year in college algebra I routinely went to the board to explain to the class what the teacher was trying to impart.

I’m not trying to brag, or even humblebrag. I just happened to be good at the things that are valued and rewarded in schools—memorization, logic, manipulating words, grasping principles and their application, seeing connections between disparate events or ideas.

These traits get you branded as “smart.” Indeed, at least when I was in school, they were pretty much the only cited characteristics of intelligence. This was an era where this scene from Broadcast News, with Holly Hunter lamenting how awful it can be to be the smartest person in a room, made perfect sense.

Fast forward to 2023. One of my sisters and her husband and I were discussing the Times’ Spelling Bee puzzle and similar smartypants games. My brother-in-law and I love Spelling Bee. My sister said it makes her feel stupid.

I did a poor job at the time explaining why she shouldn’t feel that way. So I’ll try again now.

There are many more types of intelligence than the type that “smart” high school students have (which can be shallow, mechanical, and performative). My sister and one of my running partners are off the charts in empathy, compassion, sensing and remembering what others care about, and other aspects of making people feel comfortable, valued, and loved. It’s no coincidence that both devoted their careers to social work.

Unfortunately, this isn’t a field that society values or that’s seen as a go-to choice for “smart” people. Yet what is intelligence in general but knowing how best to navigate a given situation? In my sister’s and friend’s work, their intelligence can have life-changing consequences. In mine, ooh, it means I can explain the difference between PEBA and Pebax.

Put another way, it’s wrong to say Person A is smart and Person B isn’t. Instead, both are smart in their own ways. Even our current president has a certain feral intelligence for survival. That doesn’t make it (or him) admirable, but what does it say about us if we simultaneously think he’s a moron and is ruining the world?

What’s important is to know what kind of intelligence comes naturally to you and what kind you’re bad at, and then, as warranted, try to get better at the hard stuff. Below is what greets guests when they sit down to dinner at our house. I can fold cutesy napkins only because of hundreds of hours of practice during my tenure as the world’s best-educated busboy.

I also have an inherent deficit in the emotional intelligence that’s genuine and natural in my sister and friend. Oy, the hours I’ve wasted and the hurt I’ve caused by treating conversations like a debate club competition instead of a way to really understand someone. Improving in that area is something I’ve had to work hard at.

“It’s more important to be nice than right,” I frequently remind myself. Trying to live that idea might be why a figurative knot I tied will, Zeus willing, mark its 28th anniversary next month.