PhDNF

When quitting is the right choice.

Another thing I like to bore people with is the sunk-cost fallacy. This is thinking that you should stick with an undertaking that you’ve expended significant resources on even when bagging things is the wiser choice.

A classic example is the Concorde supersonic jet. By the time the first transatlantic Concorde flight occurred in 1977, the project was years behind schedule and billions over budget. But even when the Concorde’s profitability became improbable during the many years of development, proponents plowed ahead. After all, to stop then would mean having wasted all that time, effort, and money! This line of thinking, alas, has often been used to prolong wars—stopping now would mean X number gave their lives in vain, etc.

I didn’t know about the sunk-cost fallacy when I started a PhD program in 1988. (I had other ways to bore people then.) Yet I didn’t succumb to it during what might be one of the shortest PhD stints in academic history.

The executive summary: I dropped out halfway through the first semester when I realized I didn’t want to be in school and accumulating debt for several more years. (Skip to More Subtle Sunk Costs below if you’re set on my bio details for now.)

The longer version: “What are you going to do with a religion degree?,” my senior year college roommate asked. “I don’t know, work for a running magazine?,” I replied, well aware that he had a good point and that I had zero interest in or plans for entering the work force at age 22. I kicked the life-choices can down the road for two years by immediately entering a masters program after college. The seminary where I went was partly funded by the largest Lutheran denomination, so one year’s tuition, room, and board cost something like $3,500, which I could make during summers and school breaks at a restaurant a mile from my parents’ home.

Two years passed quickly and I was no closer to knowing what I wanted to do. Even if I’d had an idea, I wouldn’t have known how to make it happen. So, I figured, why not stay in school? I was good at it and enjoyed it. A PhD program would be an intellectual feast, at the end of which the world would come bidding for the services of someone with a doctorate in American studies and a specialty in religious history.

It should be obvious by now that, for someone who was so into school, I failed to do my homework. I probably should have reassessed my so-called plan when I was rejected by William and Mary, where I went for undergrad. The small postcard from Harvard that might as well have had just “NO” stamped on it should also have been a clue. I wound up enrolling at George Washington University for the simple reason that it was the only program that accepted me.

The program was disillusioning. I quickly grokked that most of it would be hurdle hopping and dues paying. One class required reading more than 1,000 pages a week, which, fine, except that we never discussed or otherwise had reason to call upon what we’d read.

On a Sunday morning six weeks in, I woke at 7 panicking that I was already behind for the day. I’d taken out $8,000 in loans just for the semester, which might seem like a rounding error to those currently funding someone’s higher education, but was a big deal in 1988. There was no reason to think things would improve financially or educationally for the next however many years.

The real moment of clarity came when I thought, “If I had a job, I could enjoy Sunday mornings.” When I realized I was fantasizing about full-time employment, I knew it was time to exit. I informed the department that week that I was dropping out immediately.

More Subtle Sunk Costs

Most sunk-cost situations aren’t this obvious or life-changing. A go-to quotidian example used to be that you buy a movie ticket and sit tight until the credits even though you’re hating the movie. To leave early would be to waste money, right? (The movie example no longer really pertains with streaming as the default viewing mode. If anything, as with so many things encountered (seemingly) for free amid infinite choices, that financial model might lead to too-easy abandonment. This curse of contemporary life merits a separate post.)

So let’s use a concert as an example. Last spring, Stacey and I eagerly attended a recital by the classical-cum-modernist keyboardist Conrad Tao. We had seen him play a couple songs with the Oshima Brothers and were wowed, and we were excited to see him in a program of his choosing.

It, uh, wasn’t a peak experience. The selections and their execution felt like we were watching a highly proficient player practice. But even when given the chance to politely exit during the intermission, we hung in there. Maybe the second half would be a lot better. Plus, those tickets weren’t cheap! So we sat ourselves back down and counted the notes until the final chord faded.

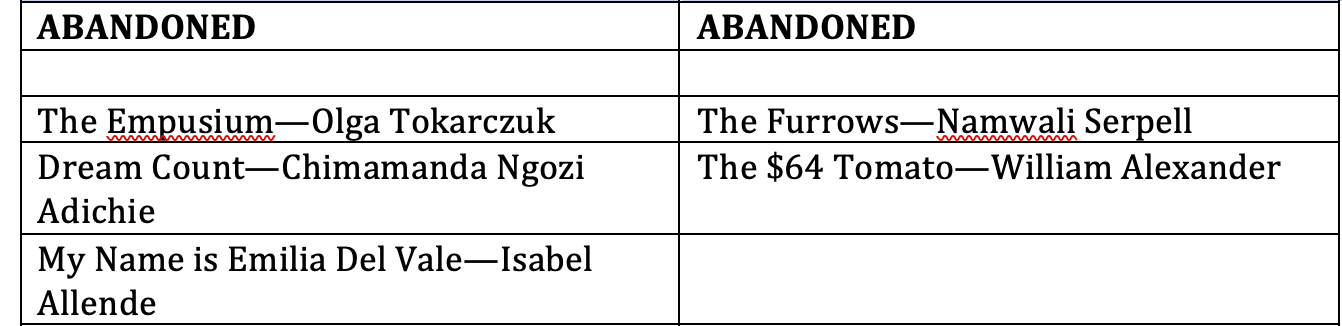

Staying was particularly silly because we’re pretty good about abandoning books that have met the initial should-I-keep-reading threshold but then fail to hold our interest.1 We’re so good at it, in fact, that our books-read-this-year list includes a DNF section; 2025’s in-process list is below, with Stacey’s on the left, mine on the right.

Some of this irrational behavior probably stems from guilt about quitting. Seeing things through builds character, quitting once will make it easier to do the next time, blah, blah, blah.

Being lifelong endurance athletes only increases the internal pressure not to quit. “Winners never quit, and quitters never win,” we’ve all been told by a Vince Lombardi devotee.

To which a reasonable retort is: Are you familiar with Tamirat Tola? Here are some of his marathon results this decade:

2022 world championships: 1st in championship record

2023 world championships: DNF

2023 New York City: 1st in course record

2024 London: DNF

2024 Olympics: 1st in Olympic record

Now, I don’t know how much Tola has studied the history of the Concorde. But he clearly knows that cutting your losses and moving on is a valid strategy that doesn’t deform you into a chronic quitter. Tola appears to be particularly good at making in-the-moment calculations about what psychologists call decisional balance and what the rest of us call weighing the pros and cons of a situation. Here are some sample decisional balance sheets; maybe you could print one out and tuck it in a pocket for your next marathon!

Anyway, thanks for sticking it out until the end. I hope you don’t consider your time here a complete sunk cost.

Stacey is a true hero in this regard. She gave up on Don DeLillo’s White Noise with like 10 pages to go.